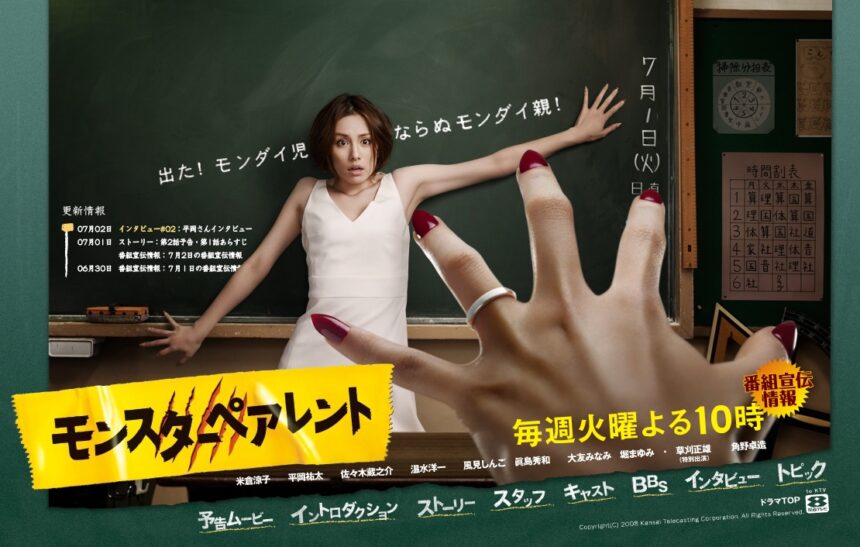

On With The Show!

In Monster Parent, Yonekura Ryoko plays Takamura Itsuki who is an ace lawyer for a well-established firm. Even though there are high profile reputations and billions of yen on the line when she is at the negotiation table, she is a woman who always accomplishes her cases with speed, precision, finesse and a pleasant but unflappable nature. She speaks her mind and can silence even the most intimidating businessmen with a glance, a word, or a smile, depending on her mood. She has never experienced stress and she has never lost a case …

… at least not until she agrees to a favor of helping the Board Of Education.

One thing that I find absolutely fascinating about the character of Takamura-sensei is that she is, simultaneously, both the “normal” and “the other” in this drama.

First I need to explain something about the word “normal” …

The word “normal” is the most useless word in the English language. I dislike the use of it in general and most especially in psychology it should NEVER be used. Why? Because the word presupposes that there is the possibility of ONE existing standard for which the definition is based. There is no such standard. The world is diverse culturally, politically, religiously, and philosophically and guess what … so is each PERSON who lives within that world. By whose definition then is the word “normal” derived? The majority? That assumes the majority is capable of an absolute infallibility. How in the universe is that possible? “Normality” is relative, which means it depends – for it’s significance – upon the nature of something else. The nature of things is forever changing due to infinite influences from everything around it. Ergo, there is no way to define the word “normal” in a way that universally describes any creature or concept on this planet due to the simple fact that everything is in a constant state of evolution.

So based on that … why did I just use it?

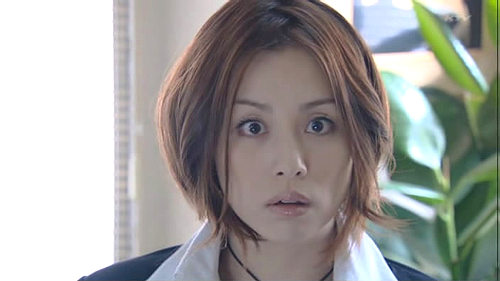

The Internal Gaijin

When I say that Takamura-sensei is “normal” I mean that according to the current rigid nature and structure of Japanese conformist and social standards, Takamura-sensei has acceptable behavior and communication for her social position, job status, and authoritative role. She is appropriately characterized. She is un-unique. That is what I mean by using the word “normal” to describe her character. On the flip side of that, according to the same standards, she is also “the other” when she becomes a observer with the Board Of Education.

She is an outsider. She doesn’t belong. Her presence doesn’t fit with, or create harmony in, the group dynamic. She is considered rude, insensitive, inappropriate, and very KY. (Short form of “kuuki ga yomenai” which literally means “cannot read the air”. It refers to someone who is bad at reading the atmosphere of a situation or is completely out of touch with the common group.) She is a foreigner in this educational environment, a gaijin.

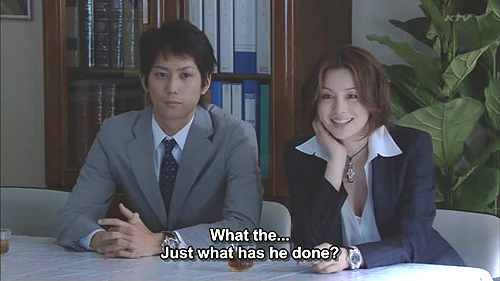

The totally ingenious part of this setup is that the audience can then relate to Takamura-sensei on multiple levels and they are able to see situations from dual positions of understanding. Takamura-sensei is both the “collective common sense of the Japanese people” while at the same time being the “inconsiderate and flippant gaijin who doesn’t understand the delicate social balance”. This goes along perfectly with the clear negative duality in that the issues brought up in the drama do not have definitive answers and sometimes no discernible party at fault – something a lawyer like Takamura-sensei expects and needs to do her job. Instead, like the very real issue of Monster Parents in the Japanese school system, the roots of the problems go deeper than that which can be probed by loggerheaded parent/teacher/principal meetings that result in something akin to external stalemates or communicative constipation.

From a psychological and sociological perspective alone, this drama is so full of rich, tasty goodness it’s like a 3 Musketeers bar! Well, actually, let’s be honest. I guess given how the icky, rancid subject matter makes you feel while you watch it, Monster Parent is more like that whale that exploded in Taiwan back in ’04.

Monster Parents Are Real

I have heard about the Monster Parent syndrome for a long time now. I have read about it, I have heard about it from friends of mine who teach in Japan, and I have experienced my fair share of Monster Parents on the American end too. I have sat in horror, just like Takamura-sensei, as the only person with a logical mind in the room, listening to adults say the most shocking and disturbing things.

Monster Parents exist everywhere, not just in Japan. This drama, however, addresses the issue of how the Japanese school system has been affected by it’s new open policy to allow parents more “say” in how the school educates their children. In a society that embraces conformity as a necessary construct for harmony and success, parents have previously had no rights to speak on issues surrounding their children in school, or have simply stayed respectfully quiet. It is understandable then how now, thanks to this new change, parents are coming forward to get more involved in their child’s education. The problem is of course, how much is too much, and how do you close a door you previously opened without further backlash? I am reminded of a beautiful line in the Korean version of Boys Over Flowers where the mother says something like: “You can’t retrieve a card once it has been played”. In other words, I hope you know what you’re doing because once the pebble starts rolling down the mountain, it may quickly become an avalanche. Said avalanche, that has clearly been a destructive force to the Japanese educational system, students, and teachers alike, is the subject of Monster Parent.

Monster Parent presents it’s content by pulling actual incidents from the headlines, as well as, most likely adding their own uniquely written ones. It seems, from the few episodes I have watched, that a lot of these incidents, if not all, are pulled from a book that was published last year by Yoshihiko Morotomi, a professor at Japan’s Meiji University.

Yoshihiko-sensei illustrates hundreds of incidents of the Monster Parent phenomena, two of which have already been dramatized within the first few episodes of the show. One of the situations, covered in several newspapers in Japan and the United States, talks about how a Japanese school put on the play “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (in the drama it is “Little Red Riding Hood”) and how, due to pressure and harassment from parents and guardians, all 25 students were cast as Snow White. There were no dwarfs and no witch because such concepts of, let’s say “deformity” or “less than perfect appearance”, would be insulting to the children (and their parents) and also it would be an injustice to the other children to select just one girl to play the title/star role. Now, those of you who have just thrown your hands up in the air and said, “Good lord that’s nuts”, I want you to take a step back from yourself and think about Japanese culture, traditions, and beliefs. Now draw a connecting line between all those things and follow the logic of how such a situation could have inevitably come to pass.

While I cannot begin to address all of the factors that created this distressing zeitgeist happening in Japan, I can talk about the communication factor that I believe is at the heart of the problems depicted semi-fictitiously in the drama.

Let me try to sum up the COMSIT (communication situation) in Monster Parent: The now secondary authority figures (the teachers and principals) are failing at their ability to acknowledge the new authority (the parents) and the newly developed one directional communication system they have chosen to adopt. To help the teachers and the principals get adjusted to this new system, they involuntarily get tongue whipped (and not even in a nice way), insulted, bullied, spayed, neutered, and psychologically tortured until they concede to recognizing their demotion … oh yeah, and then they have to apologize … loudly.

Yep, that about sums it up! When I watch this horrendous excuse for communication depicted in Monster Parent, all I can hear out of the parents’ mouths is Strother Martin saying, “What we have here … is a failure to communicate!” and all I can hear out of the teachers’ and principals’ mouths is LeVar Burton, bloody and defeated, saying, “My name is Toby …”